You close another incident report and feel that nagging doubt: Did we actually fix anything?

Someone wrote "human error," a refresher was scheduled, and the case was closed. A month later, a similar incident occurs with a different person, following the same pattern.

The issue isn't effort. It's the frame. We keep treating symptoms, not the system.

Tripod Beta changes that. It helps you map what happened, identify which barriers (controls) failed, were missing, or were effective, and understand why the system allowed that failure from the moment of action to the conditions and decisions that led up to it.

In this guide, you'll learn exactly how to run Tripod step by step, plug findings into BowTie, and turn reports into real prevention.

What is Tripod Beta?

Tripod Beta is a barrier-based incident investigation method designed specifically for high-risk, complex incidents. It is a very extensive and detailed method, and training is highly recommended when using Tripod Beta.

The method follows three fundamental questions:

- What happened? - Identifying the chain of events

- How did it happen? - Identifying which barriers failed to stop this chain

- Why did it happen? - Analysing the causation path for each failed barrier

It traces causes from the immediate human action or error through the working conditions that enabled it to deeper organisational failures, helping you move past "human error" and into system design and decision-making—the level where repeat incidents are actually prevented.

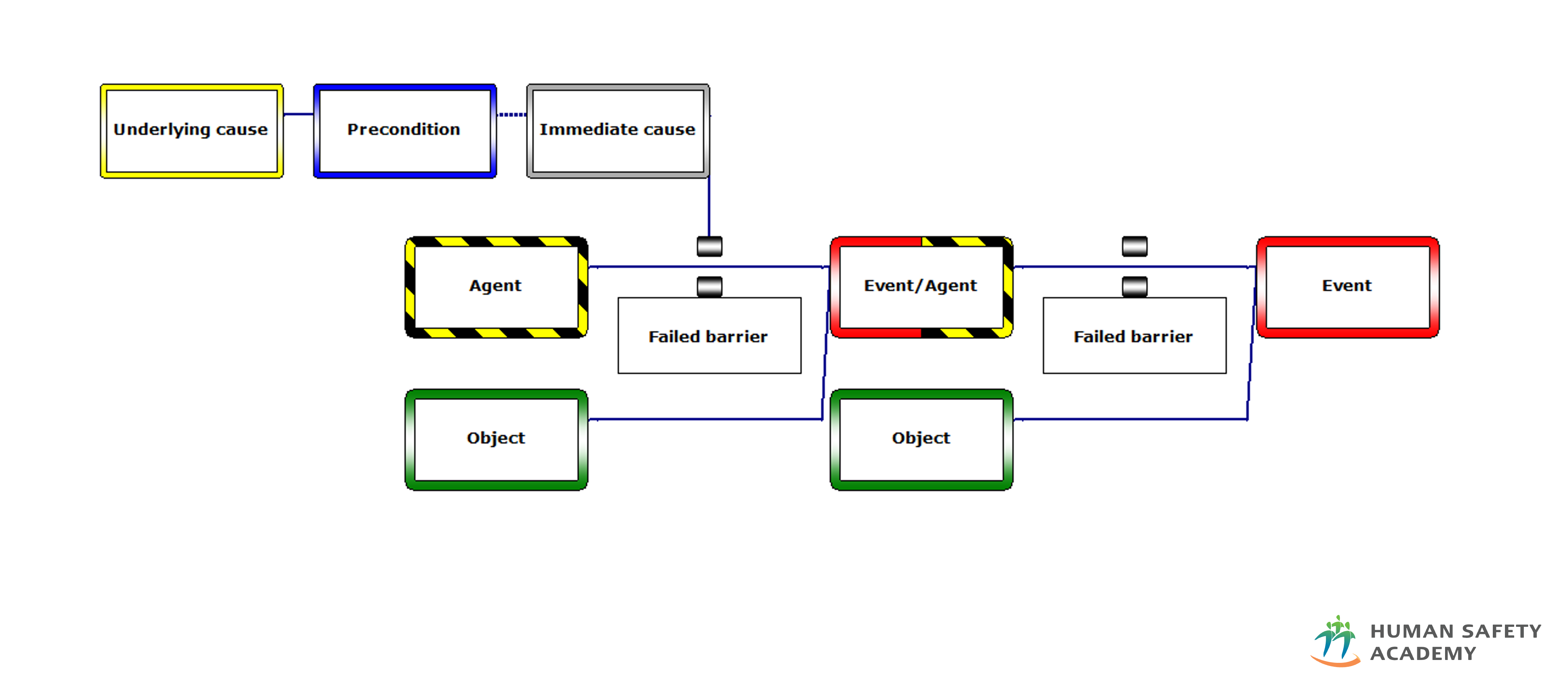

The core of Tripod Beta's causation analysis follows three levels:

- Immediate Cause (IC) - The direct human action or error that caused the barrier to fail

- Preconditions (PC) - The working conditions and circumstances that enabled the immediate cause

- Underlying Causes (UC) - The organisational failures that created those preconditions

This IC → PC → UC chain ensures you fix the system, not just the person.

How it fits in day-to-day work

- It begins with a clear sequence of events (no drama, just facts).

- It focuses on barriers (engineering, procedures, supervision, alarms, PPE) and their real-world performance.

- It forces a clean IC → PC → UC chain so your actions fix the system, not just the person.

- It uses the same barrier-based logic as BowTie risk management, so findings plug straight into proactive controls and assurance.

Why Tripod Beta matters

Today's incidents don't stem from a single bad decision; they result from complex systems of interconnected choices. Tripod Beta helps teams everywhere turn that complexity into clear learning and durable prevention. In this section, we'll explain why Tripod Beta matters right now, demonstrating how a barrier-first approach enables global teams to learn from complex incidents, meet regulatory expectations, and present real prevention across sites.

1. Incidents are more complex than ever

Modern operations involve contractors, software, machines, and tight timelines. Small gaps line up quickly. Tripod Beta keeps everyone focused on the barriers and controls that actually prevent harm, so you can see where protection has failed and fix it quickly.

2. Regulators and customers expect defensible learning

Across the US, EU, and APAC, "human error + re-training" isn't enough. Tripod Beta shows why a barrier failed and what system factors must change. That makes your investigation credible and easier to stand behind.

3. Budgets are tight; prevention must show ROI

Leaders fund what they can see. Tripod Beta links actions to specific barriers and assurance tasks, allowing you to demonstrate which controls have strengthened and how repeat risk has decreased.

4. Teams change, knowledge shouldn't

New hires, turnover, and multi-site work make consistency hard. Tripod's simple Agent–Object–Event and IC → PC → UC approach provides every site with the same playbook, ensuring that learning sticks even when personnel rotate.

5. Digital ops need structured findings

Sensors and logs are useful only if your conclusions are structured. Tripod outputs plug straight into BowTie and dashboards, turning lessons into visible, trackable prevention across plants and regions.

6. Near misses are your cheapest wins

When a barrier "almost" failed, Tripod explains why it nearly broke and what needs to be strengthened before a serious loss occurs. You fix the system while the cost is still low.

7. Global consistency, local relevance

Whether you run a single facility or a global network, Tripod scales to meet your needs. One method, one language adapted to the local context, so your prevention story is consistent worldwide and meaningful on the shop floor.

When to use Tripod Beta in incident investigations

Tripod Beta is best when you need a clear, defensible way to understand complex events and stop repeats across the organisation. Use it when:

- Risk is high or could have been high (HiPo). Even a minor outcome with serious potential deserves deeper learning.

- Multiple factors overlap. People, equipment, procedures, environment, and timing all interact to create a complex system.

- Patterns are repeating. Similar incidents or near misses appear across shifts, teams, or sites.

- A near miss exposed weak controls. Barriers worked "just enough" for the ideal moment to learn.

- Stakeholders expect rigor. Legal, regulatory, client, or leadership scrutiny requires a robust method.

Use lighter tools when:

- The cause is obvious, the risk is low, and a local fix solves it (e.g., a mislabeled bin corrected immediately).

How Tripod Beta improves investigations (the three-stage map)

Before we dive into the steps, picture this: you're trying to explain an incident to leaders and frontline staff quickly, clearly, and without blame. Tripod Beta provides a simple map that anyone can follow. Three moves, same order every time, and you end with actions that actually make controls stronger.

Stage 1: Map what happened (the sequence)

Start by laying out the incident as short, factual trios: Agent – Object – Event. The logic flows as: the Agent (source of change or hazard) works on the Object (what is being changed), which results in the Event (the change of state).

Keep it concise, without opinions; just record what carried risk, what was exposed, and what changed.

Example: "Pressurised line (agent) works on technician's hand (object), resulting in contact with solvent spray (event)."

Key concepts:

- An Event is the unwanted disruption in the process due to the uncontrolled release of the Agent—it is the state in which an Object has been changed (affected) by the Agent

- An Agent has the potential to change (affect) the Object and contains energy that should have been controlled (can be seen as a hazard)

- An Object is that which has been changed (affected) by the released Agent, described as it was before the change

Build 3–6 of these trios to show the path the hazard took. When the sequence is clear, everyone can see the same mechanism, no arguing over narratives.

Stage 2: Check the controls (the barriers)

For each step in the sequence, list the barriers that should have blocked the agent or protected the object. Barriers can be placed in two locations:

- Between the Hazard/Agent and the Event (preventing the agent from creating the event)

- Between the Event and the Object (preventing the event from affecting the object)

Common barrier types include engineering controls, procedures/permits, supervision, alarms/interfaces, and PPE.

Label each one as:

- Effective: worked and stopped the hazard

- Failed: existed but didn't work when needed

- Inadequate: a rare category used when a barrier functioned as intended by its design specifications, but was unable to stop the sequence of events—indicating an issue with the design specifications themselves

- Missing: should have been there but wasn't

This is where weak spots become obvious. You're talking about controls, not people, and you can point to exactly where protection slipped.

Stage 3: Explain why it failed (IC → PC → UC)

For every failed, inadequate, or missing barrier, write a short cause chain following the Tripod Beta causation model:

Immediate Cause (IC): An action or omission of a person or group that causes a barrier to fail. Immediate causes defeat barriers and occur close to them in time, space, or causal logic. Incidents happen when people make errors and fail to keep barriers functional or in place—these errors are Immediate Causes, also called substandard acts. Note: Only ONE Immediate Cause is allowed per barrier.

Preconditions (PC): The detrimental influences on people and their resulting 'state of mind' that increase their likelihood of performing a substandard act. Preconditions visualise the situation that stimulated the Immediate Cause—they describe the context in which the Immediate Cause becomes more probable. This can relate to supervision, training, instructions, procedures, equipment condition, workload, communication, and other factors. Preconditions explain why the person or group had the belief or perception that their act was acceptable or expected.

Underlying Causes (UC): The organisational deficiency or anomaly creating the precondition that caused or influenced the immediate cause. Underlying Causes operate at the system level and always involve the organisation. They are not incidental but have been present in the system for a long time before the incident occurred—they are latent failures in the organisation. These represent the deeper organisational factors that allowed the conditions for failure to exist.

Basic Risk Factors (BRFs): Underlying Causes are categorised using eleven Basic Risk Factors that represent the working environment in 11 dimensions:

- Design (DE) - Deficiencies in layout or design of facilities, plants, equipment, or tools

- Hardware (HW) - The physical equipment and materials

- Procedures (PR) - Unclear, unavailable, incorrect, or otherwise unusable standardised task information

- Error-enforcing Conditions (EC) - Factors such as time pressure, changes in work patterns, physical work conditions that promote human failure

- Housekeeping (HK) - Tolerances of deficiencies in conditions of tidiness and cleanliness

- Incompatible Goals (IG) - Failure to manage conflict between organisational goals, formal and informal rules

- Communication (CO) - Failure in transmitting information necessary for safe and effective functioning

- Organisation (OR) - Deficiencies in either the structure of a company or the way it conducts its business

- Training (TR) - Deficiencies in the system for providing necessary awareness, knowledge, or skill

- Defenses (DF) - Failures in the system, facilities, and equipment for control or containment of sources of harm

- Maintenance Management (MM) - Failures in the system for ensuring technical integrity

These BRFs help systematically identify organisational deficiencies and ensure comprehensive root cause analysis.

This structure keeps the analysis factual, fair, and repeatable. The relationship flows: UC creates PC, which increases the likelihood of IC, which causes the barrier to fail.

Tripod Beta vs Traditional Root-Cause approach

Traditional "root-cause" models often stop once a single error seems plausible. Tripod Beta goes further—it systematically analyses which barriers broke during an incident, the error or mistake made, the working environmental aspects that encouraged this, and finally the latent failure in the organisation that caused that mechanism.

The Tripod Beta analysis process follows three steps:

- Identify the chain of events preceding the consequences

- Identify the barriers that should have stopped this chain of events

- Identify the reason for failure of each broken barrier, broken down into the human failure (Immediate Cause), the working environmental aspects (Preconditions), and the latent failure in the organisation (Underlying Cause)

The result is actionable prevention at the organisational level, not another corrective memo focused on individuals.

Tripod Beta in action: simple, real-world examples

- In manufacturing, a near-miss chemical splash revealed the wrong gloves were in use. Tripod showed the issue wasn't carelessness but the absence of a glove-selection standard and weekend supervision.

- In healthcare, an unacknowledged lab alert traced back to alert fatigue and unclear escalation—system issues, not individual failure.

- In energy, an unexpected equipment restart highlighted weak communication and a missing cross-contractor isolation standard.

Different contexts, same logic: identify the barrier, trace why it failed through IC-PC-UC, and strengthen the system.

Why this approach works

Tripod Beta succeeds because it is:

- System-focused — examines barriers and organisational context, not blame

- Structured — every case follows the same IC → PC → UC logic, ensuring consistency

- Integratable — findings plug directly into BowTie and assurance dashboards

- Practical — creates fixes tied to real barriers with measurable improvement

- Barrier-based — uses the same barrier thinking as risk assessment, completing the learning cycle

The method turns investigation from administrative closure into genuine prevention by addressing the organizational factors that create the conditions for incidents.

Related methodology: If you're looking for a more streamlined barrier-based investigation method, consider Barrier Failure Analysis (BFA)—a practical approach that shares Tripod Beta's IC → PC → UC causation model but offers greater flexibility for different incident types and investigation depths.

How the Human Safety Academy can help

Human Safety Academy (HSA) specialises in barrier-based methods — Tripod Beta, BowTie, and Barrier Failure Analysis — and teaches them through hands-on workshops, simulations, and coaching.

Teams learn to conduct interviews without blame, apply the Agent-Object-Event and IC-PC-UC logic on real cases, and link findings directly into BowTie risk controls.

HSA training follows internationally recognised standards: Bronze (practitioner), Silver (advanced), and Gold (lead investigator) accreditation, maintained by the Tripod Foundation and published by the Energy Institute.

Next steps

- Try mapping a recent near miss using Agent – Object – Event trios

- Identify which barriers failed or were missing, and ask the three questions: What happened? How did it happen? Why did it happen?

When investigations shift from "who's at fault?" to "what must be stronger?", learning sticks, operations stabilise, and safety becomes part of everyday work.